William Parkes of Newport – the last survivor of the Welsh Bantam Brigade

By Peter Brown

© Peter Brown 2025

William Parkes was born on 18 January 1896 in Newport, South Wales. His family lived in the Pill (Pillgwenlly) dockland area, where he was baptised at Holy Trinity Church on 16 February. He was the fifth of 11 children of an iron moulder called James Parkes and his wife Maria (nee Mills). In 1901, the family lived at 11 Jeddo Street, although the Johns’s Newport Directory for 1905 lists them at number 15. William attended Bolt Street School and was listed as a hairdresser’s apprentice when they lived at 106 Raglan Street in 1911.

World War I

William and his three brothers enlisted after the war started in July 1914. James signed up for the infantry in the South Wales Borderers a month after the war began. Thomas became a sapper in the Royal Engineers and, in 1923, emigrated with his wife Mary to California, where he died in 1982. Reginald joined the Royal Navy in 1917 and stayed until 1945. William recalled, "My youngest brother served in both World Wars. His ship was torpedoed in the Second World War.”

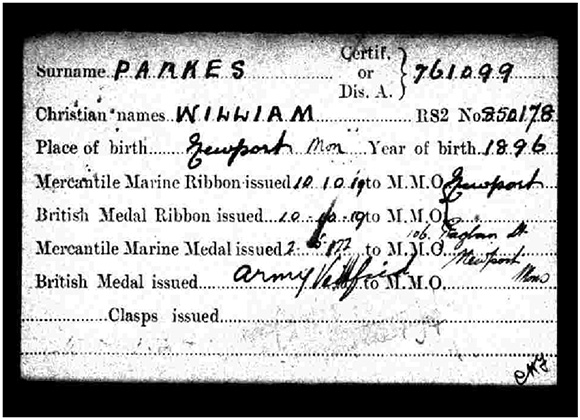

William tried to join the Royal Navy at the outbreak of the war but was turned down because he was too small at 5’ 5” (1.65 m) and 140 pounds (64 kg). In a later interview, he confirmed that he served in the merchant navy, and his medal card for service during the war is held at The National Archives. Newport was well known for providing the crews of merchant ships, but unfortunately, few records have survived.

Medal Card of William Parkes from the Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen

Medal Card of William Parkes from the Registrar General of Shipping and Seamen

(From The National Archives, reference BT 351/1/109162)

William left the merchant navy and joined the 12th (Service) Battalion (3rd Gwent) of the South Wales Borderers, when it was formed in Newport in March 1915; later, it became part of the Welsh Bantam Brigade. The Welsh National Executive Committee formed that battalion for recruits from 5’ (1.52 m) to 5’ 3” (1.60 m); however, progress was slow initially as many Monmouthshire men had already enlisted in the 17th and 18th (Bantam) Battalions raised in Glamorganshire.

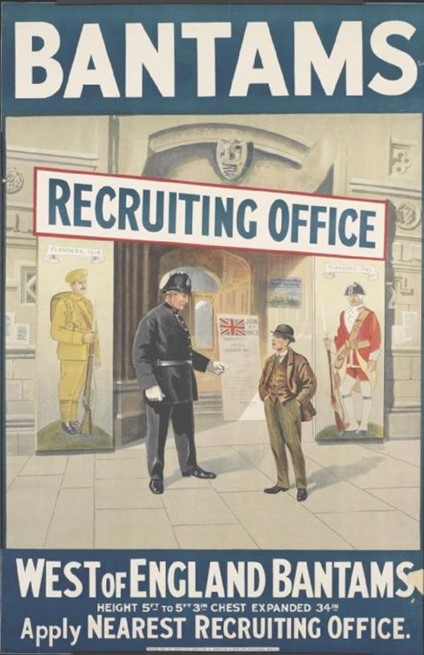

The term ‘bantam’ is derived from the name of the seaport city of Bantam in Java, Indonesia. European sailors who restocked on live fowl for sea journeys favoured the small native breeds of chicken in Southeast Asia, and any such small poultry became known as bantams. By the early 19th century, the term became used for a small person, and in the later 19th century, it was also applied to a weight class in boxing for smaller men, perhaps deriving from the birds, which are small but aggressive and bred for fighting.

A Bantams recruiting poster from WWI

(In the public domain – reproduced by kind permission of the Imperial War Museums)

The first Bantam Battalions had been formed in 1914 to accommodate small men with a maximum height of 5’ 3” (1.60 m); William was 2” (0.05 m) over this limit. Previously excluded from fighting units, these men were allowed to enlist provided they were grouped into special ‘short stature’ units. In some cases, recruits were underage because it was easier to lie about how old they were in a battalion for short men. By the war's end, 29 Bantam battalions had been created across one Canadian and two British divisions, totalling over 50,000 Bantam soldiers. Officers were typically of ‘normal’ size, and perhaps the most famous of those was Bernard Montgomery, Brigade Major of the 104th (Bantam) Brigade and later Field Marshal Montgomery.

Captain Bernard Montgomery (right) with Brigadier-General J. W. Sandilands, commander of the 104th Brigade, 35th Division. Montgomery served as the brigade major with the 104th Brigade from January 1915 until early 1917.

(In the public domain – reproduced by kind permission of the Imperial War Museum)

Among the most famous Bantam soldiers was Sir Billy Butlin, who later founded Butlin’s holiday camps. He was a teenager living in Canada who reluctantly volunteered for service in 1915, aged 15. He saw action in places like Vimy Ridge, Ypres, Arras, and Cambrai as a bugler and stretcher bearer in the 216th (Bantams) Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force. His holiday empire was inspired by a trip to Barry Island in his twenties, during which his landlady locked him out of his B&B all day. In 1965, he decided to build the last and smallest of his holiday camps there.

An official photograph of Billy Butlin was taken shortly after enlistment in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in 1915.

(In the public domain)

The Welsh Bantam Brigade trained at Prees Heath in Shropshire in July 1915. In September, they moved to Aldershot, where William trained as a machine gunner. Subsequently, the formation was renamed the 119th Brigade, 40th Division. In December 1915, they moved to Marne Barracks at Blackdown Camp in Surrey. He also undertook the Physical Training Instructors Course in the Officer Cadet Battalion from 28 January to 9 February 1916.

The Battalion landed at Le Havre as part of the 119th Brigade in the 40th Division on 2 June 1916 for service on the Western Front. Welsh poet and language activist Saunders Lewis also served in the 12th Battalion during World War I. Its first serious action was in April 1917, when the 40th and 8th Divisions attacked Gonnelieu, southeast of Cambrai. The 12th Battalion carried the formidable defences of Fifteen Ravine with great gallantry and skill, securing all their objectives for 26 killed and missing and 45 wounded. They counted 40 dead Germans in the position and many more beyond it. This was William’s toughest action, and by the end, he was commanding his company after all the officers were killed.

William Parkes in Army uniform.

(Image found in the Napa Valley Register, December 15, 2000.

Reproduced under ‘fair use’, courtesy of the California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside, http://cdnc.ucr.edu)

When wounded in the leg by shrapnel on 4 April 1917, two days before the USA joined the war, he urged his dresser to bind him up tightly so he could return to his men: “Wrap it up, wrap it up tight, I gotta get back in there,” he recalled more than 80 years later. However, his leg collapsed when he tried to stand; it was only when he stood up that he realised he could not walk. After his leg injury was resolved, he became an instructor at Sniggery Camp outside Liverpool and started training for a commission; however, he concluded that he was not educated enough and returned to the Front.

The 12th Battalion performed a successful raid in May 1917, winning a Military Cross and eight Military Medals. They remained in the same sector throughout the summer, distinguishing themselves by capturing German patrols and by several raids. In one of these, carried out by two officers and 32 men, the Bangalore Torpedo, used to blow a path through the wire, failed to explode. The commanding officer cut the wire himself, led his men through the second trench and brought them out with only two casualties after inflicting heavy losses on the enemy.

Although 2” (0.05 m) taller than the prescribed height when he joined, William and two other men regularly went out on night reconnaissance patrols together in No Man's Land because it was commonly believed that their shorter stature made them harder to see. He specialised in what he called ‘reconnoitring’, and in 2000, he stated: “Us little guys could hide much better than the tall guys.” His most disturbing wartime experience was a lone patrol on which he brushed the snow from the face of a dead German in a crater and found that it strongly resembled that of one of his brothers…

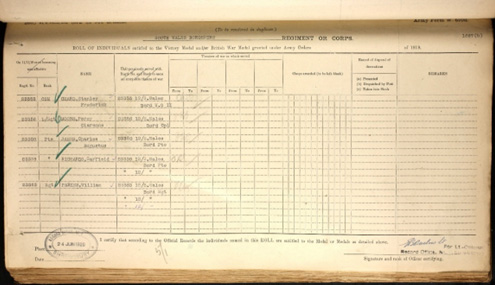

Roll entry for entitlement to the Victory Medal and British War Medal.

Sergeant William Parkes is listed as 23363 12/S. Wales Bord Sgt.

He was discharged from service in London in February 1919 and worked on the docks, presumably in Newport.

To the USA

William emigrated to America on the Adriatic, leaving Southampton on 6 October 1920 and arriving in New York on 15 October. At first, he stayed with relatives in Pennsylvania, where he was employed in the coal mines. His ‘Naturalization Declaration’ was submitted in Chester, Pennsylvania, on 20 April 1921.

He visited the San Francisco Bay area a year later and decided never to leave. He first worked as a plasterer, nicknamed ‘The Speedy Welshman’ by the San Francisco Chronicle when he began playing soccer in his spare time with the San Francisco Barbarians, who won the state championship in 1922–3. After he was involved in a scuffle, the paper changed this to ‘The Battling Welshman’.

He settled in Napa Valley in 1932, becoming an orderly and occupational therapist at the Napa State Hospital and superintendent in charge of outpatients' day jobs. While there, he met his future wife, Dolly Nelsen, who was then married to Roy Gardner, a famous mail train robber and jailbreaker imprisoned in Alcatraz at the same time as Al Capone.

Dolly Nelsen

(Photo on open access at Ancestry.co.uk)

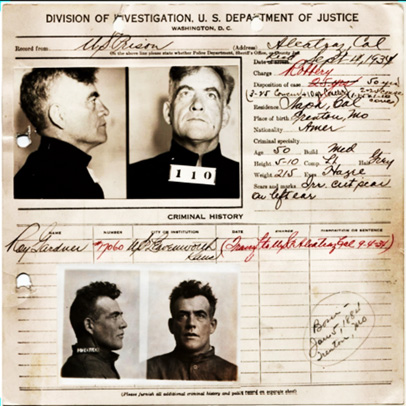

Roy Gardner

Gardner was in Alcatraz from 1934 to 1939. After being paroled in 1938, he became a guide on a tour boat that circled Alcatraz Island. In 1939, he published his autobiography, Hellcatraz, and a short film called You Can't Beat the Rap. He worked as a film salesman, and his life was represented in an unsuccessful 1939 movie called I Stole a Million, starring George Raft and Claire Trevor. In 1940, in a hotel room in San Francisco, Gardner killed himself by dropping cyanide into a glass of acid and inhaling the poison fumes. He left a note asking William to look after Dolly.

Roy G. Gardner (1884–1940) is shown in a Department of Justice photo when he transferred to Alcatraz in 1934.

(Image widely distributed on the Internet. Copyright owner unknown)

A home in Napa County

Dolly obtained an annulment of the marriage because when they married in 1916, Gardner had withheld information that he had been convicted and served time in San Quentin. William and Dolly subsequently married in Napa County in 1936. After their marriage, William helped to build a house opposite the hospital, where he lived for the rest of his life. He tried to join up with the American forces on the day of the Pearl Harbour attack in 1941 but had to withdraw after suffering a minor heart attack.

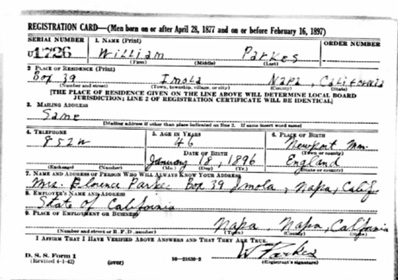

U.S., World War II Draft Registration Card for William Parkes (1942)

(Found on Ancestry.co.uk)

William Parkes in the early 1950s with Gaynor Turner Hintz, whose grandmother, Clara, was William’s sister. The photo was taken at the rear of his house in Napa.

(Photo by kind permission of Gaynor Turner Hintz)

Later Life

William retired from the hospital in 1961 and concentrated on cultivating his one-acre garden of vegetables and fruit trees, where he earned the name of ‘Farmer Bill’. The state hospital patients did much of the work for him in the garden. After Dolly died in 1979, he lived alone in their house.

He sang in the St Mary’s Episcopalian Church choir and was active with the California State Employees Association. He cautiously dabbled in the Stock Market until he considered that the risks were becoming too great. In his later years, he enjoyed visiting schools to share his century of memories with children. He attributed his longevity partly to having never smoked. He also drank for only two years as a young man, following an embarrassing incident when his family had to put him to bed; after this, he swore to himself that no one would ever again have to take care of him because of drinking.

William, who retained his Welsh accent while identifying as English, never returned to Britain. Although ‘Papa Will’ had no children, he sponsored many relatives who emigrated from England and Wales and was close to his nieces and nephews and their grandchildren and great-grandchildren. He sponsored the emigration of a niece who married an American and later looked after him.

William Parkes, in later years

(Photo on open access at Ancestry.com)

Legion d’Honneur

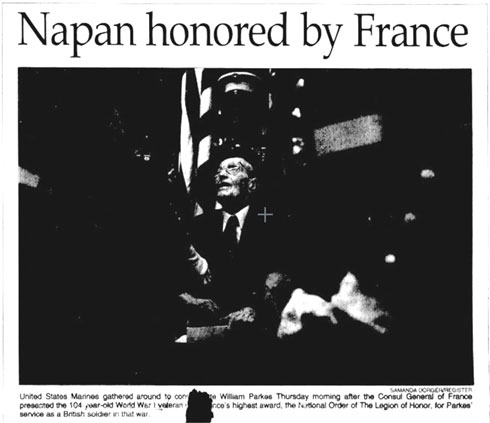

William had joined the Royal Canadian Legion because no British Legion branch was nearby. In 2000, he joined other World War I veterans in receiving the Chevalier de la Legion d’Honneur, which the French government had authorised two years earlier to honour the Allies and mark the 80th anniversary of the signing of the Armistice, which ended the Great War on 11 November 1918. Gerard Coste, the French Consul General in San Francisco, pinned the green and white medal on William as he sat in his wheelchair in Napa on Dec. 14, 2000, flanked by a Marine Corps honour guard from Concord. A representative of the Fusiliers also presented him with a Royal Welch Fusiliers Millennium Plate for his historic service to the military unit.

State Senator Wesley Chesbo from the California Department of Veterans Affairs and the offices of several California politicians presented him with certificates of recognition. Colin Dixon, representing the British Consul General of San Francisco, offered thanks and recognition to William and the important place he held for everyone as one of the last remaining veterans of World War I. Dixon said, “You sacrificed. They were terrible sacrifices, and we will never forget them.” Bruce Thiesen, Interim Secretary for the California Department of Veterans Affairs, praised him for his lifetime of service, echoing Dixon's words.

Presenting France’s highest award bestowed on its citizens and foreign nationals–The National Order of The Legion of Honour–the Consul General of France, Gerard Coste, called William “A courageous soldier and a wonderful man. William Parkes, thank you for your courage and vibrant example set for young people on how to live an honourable and happy life.”

“To be in the same room with a Legion of Honour medal winner is an incredible honour. We’re so pleased you are here,” said Napa Mayor Ed Henderson.

William Parkes received the Legion of Honour on 14 December 2000.

(Image found in the Napa Valley Register, December 15, 2000.

Reproduced under ‘fair use’, courtesy of the California Digital Newspaper Collection, Center for Bibliographic Studies and Research, University of California, Riverside, http://cdnc.ucr.edu )

William Parkes died on 7 October 2002 in Napa, where he had lived for 70 years. He was an amazing 106 years old and was buried there with Dolly on 12 October in Tulocay Cemetery.

Author’s note

I first encountered information on William Parkes several years ago while researching the history of Bolt Street School, which I attended in the 1950s. His extraordinary story amazed me, and I vowed I would one day investigate further and share the results. I hope this biography is as enjoyable to read as it was to research.

I am grateful to William’s family, notably Amanda Berry (Barry) and Gaynor Turner Hintz (USA), for their help with information and photos. Celia Green from The South Wales Borderers Museum provided additional details of William’s military career, and Corinne Brown helped with the presentation.

Sources

Biographical articles

Brady-Herndon, G. (2000) ‘Napan honored by France’, The Napa Valley Register, Number 128, December 15.

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=NVR20001215.1.1&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------

https://cdnc.ucr.edu/?a=d&d=NVR20001215.1.6&e=-------en--20--1--txt-txIN--------

Glover, M. (2000) ‘Bravery in Trenches Honored / Napa man, 104, gets French award for WWI service’, SFGate, December 16.

https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/bravery-in-trenches-honored-napa-man-104-gets-2690902.php

Obituaries

Anon. (2000) ‘Sergeant William Parkes’, The Telegraph, 30 October.

https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/obituaries/1411623/Sergeant-William-Parkes.html?fbclid=IwAR0F1fkplWq_9jRgV6e-L7K52MEOYnDcN_3GOAObLJyCkHGsgFsG0SVqfjo

Anon. (2002) ‘William Parkes Obituary’, The Citizen.

https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/auburnpub/name/william-parkes-obituary?id=12015020

Anon. (2002) ‘William “Papa” Parkes’, Find a Grave.

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/6869559/william-parkes

Oliver, M. (2002) ‘William Parkes, 106; WWI Member of Welch Fusiliers’, Los Angeles Times, October 22.

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2002-oct-22-me-parkes22-story.html?fbclid=IwAR1NWpZbfmFLGuvMqOkgKPlwZEbBVI1gi3n25-xLTFJybxB4ERbVhN3AXxY

https://jesseshunting.com/threads/william-parkes-106-wwi-member-of-welch-fusiliers.18557/

'We Remember William Parkes’, Lives of the First World War, Imperial War Museum.

https://livesofthefirstworldwar.iwm.org.uk/lifestory/7005775

South Wales Borderers

Baker, C. (n.d.) ‘South Wales Borderers’, The Long, Long Trail: Researching soldiers of the British Army in the Great War of 1914-1918.

https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/order-of-battle-of-divisions/40th-division/

‘South Wales Borderers’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Wales_Borderers

Bantams

Baker, C. (n.d.) ‘The Bantams’, The Long, Long Trail: Researching soldiers of the British Army in the Great War of 1914-1918.

https://www.longlongtrail.co.uk/army/definitions-of-units/the-bantams/

de Castella, T. (2015) Bantams: The army units for those under 5ft 3in, BBC, 9 February. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-31023270

‘12th (Service) Battalion, South Wales Borderers (3rd Gwent)’, Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/12th_(Service)_Battalion,_South_Wales_Borderers_(3rd_Gwent)

Each One a Pocket Hercules: The Bantam Experiment and the case of the 35th Division, The Western Front Association.

https://www.westernfrontassociation.com/world-war-i-articles/each-one-a-pocket-hercules-the-bantam-experiment-and-the-case-of-the-35th-division/

Roy Gardner

‘Roy Gardner’, A H Alcatraz History: Where the voices of Alcatraz come to life... https://www.alcatrazhistory.com/gardner.htm

‘Alcatraz’s Most Dangerous Inmates’, Gray Line San Francisco. https://graylineofsanfrancisco.com/alcatrazs-most-dangerous-inmates/

‘I Stole a Million’, Wikipedia.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I_Stole_a_Million