Maritime History of Newport

By Peter Brown

© Peter Brown 2024

Early industrialisation in Newport, 1796-1842

Towards the end of the 18th century, the mine owners in south-east Wales saw little scope for exports due to the lack of transport facilities to connect with the quays at Newport. A similar issue faced the owners of the ironworks, such as the huge one at Blaenavon that opened in 1789, and without canals or railways, any goods had to be carried to Newport by packhorses or in carts to be transhipped for export. Despite this, the shipping at Newport continued to expand with new wharves constructed below the town bridge and quayside walls built with stone brought from Penarth.[1] The shipyards were also busy making new vessels.

No one could have foreseen at that time how industrialisation would see Newport grow through the 19th century, as the population growth mirrored the growth of shipping.

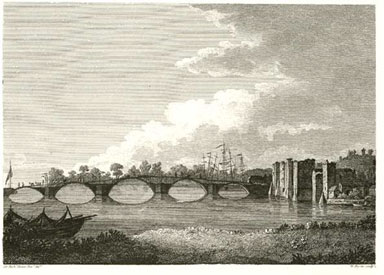

‘Bridge and Castle at Newport’ by Sir Richard Colt Hoare, published in An Historical Tour In Monmouthshire by William Coxe (1801).

This image shows the masts of the ships at the town quayside at the start of industrialisation when the first stone bridge was under construction.

The colossal growth of shipping began with the Monmouthshire Canal, authorised by an Act of Parliament in 1792. The Act included permission to build connecting tramways to pits within 7 miles of the canal and to raise £120,000 for the venture. The estimated cost was £106,000, and the enthusiasm for the scheme was such that the capital was subscribed before the Act was passed. The canal connected Pontnewydd with the quayside in Newport, with a second arm from near Crumlin travelling through Rogerstone and joining the first arm of the canal at Crindau, just north of Newport, after a distance of 11 miles.[2] Beyond Pontnewydd and Crumlin, tramroads connected the canals with the ironworks at Blaenavon and Beaufort, respectively.

The original canal to Newport terminated at a basin just to the north of the Town Pill, which had associated wharves and warehouses to allow the canal barges to be unloaded and their cargoes transhipped onto the vessels at the wharves and moored in the Town Pill.[3]

This section of the 1845 Tithe Map shows the canal basin's position close to the Town Pill, roughly where the market bus station stands today.[4]

When the canal to Newport opened in 1796, the Monmouthshire Canal Company shipped 3,500 tons of coal to the wharves on the river Usk at Newport that year. The canal was extended across the Town Pill into the area known then as Friars Fields, which required some filling in of the Pill. Plans to extensively redevelop the existing wharves in the area were drawn up but not implemented as the canal was soon extended to Pillgwenlly, and further opportunities were developed.[5]

We also have a breakdown of the tonnages of all the goods on the Monmouthshire Canal for the year commencing 9 September 1798:[6]

|

Tons |

Cwt. |

Coal |

28,091 |

0 |

Pig Iron |

11,159 |

5 |

Bar Iron |

32 |

10 |

H. Blooms |

523 |

10 |

Timber |

283 |

6 |

Lime |

153 |

5 |

Sundries |

1,743 |

0 |

Ale & Porter |

20 |

10 |

Stones |

12,353 |

5 |

Castings |

136 |

0 |

Bark |

62 |

15 |

Iron Ore |

1,955 |

16 |

Slate |

81 |

10 |

Manure |

225 |

10 |

By 1809, coal exports had grown to 150,000 tons, heralding Newport’s ascent to becoming the third-largest coal port in Britain.[7] A second Act of 1802 laid down tolls for coal, and in 1810, Hassall reported that 185,820 tons of coal were brought down to Newport by the Monmouthshire Canal and its associated tramroads, some of which must have come on the Sirhowy Railway.[8]

Although the canal's opening in 1796 led to a vast expansion of shipping, Cardiff was still the ‘mother port’, and soon after the canal opened, the merchants and traders of Newport approached the Treasury for Newport to be established as an independent port. In 1806, the Monmouthshire Canal Company also petitioned to appoint an Officer of Customs at Newport who would be empowered to “clear foreign vessels”, but there was resistance from Cardiff.[9]

The increasing demand for shipping led to wharves and warehouses being constructed further down the river from the quayside near the bridge, known as the Town Reach. This area included the inlet known as Jack’s Pill, remembered today as the location of Cashmore’s breaking yard. Before the 19th century, this area consisted of fields used for grazing and divided by ditches. It was surrounded by a sea wall, with the area between it and the river subject to flooding at high tides.[10]

Development of the area accelerated after the Tredegar Wharf Company (established in 1807) extended the canal southwards towards the Pillgwenlly Pill and created a canal basin in the area, which became Church Street, in 1808. The Company also purchased land in 1809 and constructed a mile-long road from Westgate to Pillgwenlly that we know today as Commercial Street and Commercial Road.[11] In the following years, the river banks around Pillgwenlly were filled with wharves to increase the shipping facilities. The land behind the sea wall was gradually filled in using ships’ ballast, allowing the development of the area of Pill with housing, the cattle market, works and other premises.[12] It was proposed in 1801 that 6,000,000 cubic feet of earth and ballast needed to be laid to raise the level of the area 6 feet.[13]

A letter of 1810 describes the first plan for a floating dock at Newport, sent to the Collector of Customs at Cardiff by Mr Thomas Prothero, the agent to Sir Charles Morgan.[14] The letter describes Pillgwenlly as having “nearly a third of the shipping of the Port”, based at the Tredegar Wharf in the Mill Parade area. The proposal was to construct a floating dock between there and the town quays, giving Pillgwenlly a half share of the shipping. The subscription required for the project was stated as £120,000, but there is no evidence that any progress was made in raising this.

A further attempt was made by the town in 1820 in a letter sent to the Treasury that included the following points:[15]

- That the trade of Newport has been progressively increasing during the last 25 years.

- That in 1794, the trade of Newport consisted chiefly of two or three weekly traders from thence to Bristol.

- That Newport is now one of the greatest shipping places of Coal, Iron and Tin in the Principality, and the number of Coasting Vessels cleared out in the year ended 5th July 1820 was 4211.

- That the foreign trade is also much increased, 49 cargoes of Coals, Iron and Tin having been exported in the Year ended 5th July, exclusive of 687 for Ireland.

These facts were used to make the case for Newport acting independently of Cardiff and saving the masters of the vessels from having to enter details in Cardiff for their goods from foreign parts. Still, officials in Cardiff were critical of the request and asked for details of vessels and their cargoes entering and leaving during the 12 months ended 10th October 1820, which were then supplied as follows:[16]

Ireland |

||

Number of ships |

|

Cargoes |

Inwards |

143 |

Ballast |

|

73 |

Livestock |

Outwards |

550 |

Coal |

|

16 |

Iron |

|

24 |

Sundries |

Coastwise |

||

Number of ships |

|

Cargoes |

Inwards |

3142 |

Ballast |

|

1039 |

Sundries chiefly from Bristol and Bridgwater and a few cargoes of slate from Carnarvon and Cardigan |

Outwards |

3578 |

Coal |

|

331 |

Iron |

|

272 |

Sundries |

Foreign Parts |

|

Inwards |

|

No. of Vessels |

Cargoes |

2 |

Timber from Memel (now Klaipėda, Lithuania) |

2 |

Timber from British America |

3 |

Free goods from Guernsey and Jersey |

4 |

Goods liable to Ad Valorem duty from Ireland |

1 |

Ballast from Spain |

12 Total |

|

Outwards |

|

39 |

Iron-tinned plates and a few sundries |

14 |

Iron to fill up (most of whose cargoes had been laden at Bristol) |

53 |

To France, Portugal, and the Mediterranean |

3 |

Coal to Newfoundland |

1 |

Coal to British America |

57 Total |

|

A critical factor in the growth of shipping at that time was the provision in the Monmouthshire Canal Act, where coal shipped at Newport could be delivered duty-free to the port of Bridgwater and all ports east of the Holms (Flat Holm and Steep Holm in the Bristol Channel, south-west of Newport).[17] This gave Newport a monopoly due to the financial advantages, combined with the excellent quality of the coal and the efficiency of the lading, providing duty-free shipments of 120,000 to 140,000 per year. This growth is shown in the following table for coastwise trade:[18]

Year |

Inwards vessels |

Inward tons |

Outwards vessels |

Outwards tons |

1795 |

295 |

12,190 |

243 |

11,607 |

1823 |

1,207 |

58,970 |

5,565 |

292,782 |

The minor coal exports before the canal opened in 1796 had grown to 256,795 tons by 1823,[19] and iron exports were 42,000 tons.[20] The records for 1823 also show the extent of Newport’s trade overseas. Ships entering from Ireland included 81 with cargo and 420 with ballast. There were also a few loads of cargo from New Brunswick (Canada) and Ballast from France.

The numbers of ships clearing outwards in 1823 were as follows: Belgium (6), France (2), Ex Mediterranean ports (13), French Mediterranean ports (1), Portugal (7), Kingdom of Sardinia (1), Papal Territories (1), Kingdom of Naples (6), Island of Sicily (7), Turkey (3), Ireland (737), Jersey (2), Newfoundland (7), New Brunswick (1), and New England (1). Ireland accounted for a staggering 66,243 tons of cargo exported.[21]

The expansion of the coal age created challenges for the Customs arrangements for measures and charges.[22] The unit for duty was the ‘chalder’ (a spelling variant of cauldron), an obsolete measure of dry volume based on the legal limit for horse-drawn coal waggons travelling by road, as it was considered that heavier loads would cause too much damage to the roadways.[23] Shippers had to build carts to comply with some fraction of a chalder.

The increase in coal production also increased the timber trade, with deals, battens, boards, fir, mahogany and pitprops from the Baltic and North America now becoming regular imports. In some cases in the early 19th century, the shortage of lawful quay space meant that some timber cargoes were discharged at unapproved wharves by special sufferance.[24]

The total number of vessels cleared outwards at the port of Newport in the year ending 5th of January 1831 was 8,080. Coal shipped during the same period was 466,687 tons.[25] The Monmouthshire Merlin reported that: “A friend has furnished us with the following statistical memoranda of the trade of this flourishing sea-port - Year ending December 1830 - 7163 vessels cleared out laden with 519 thousand tons of coal, 916 vessels with 106 thousand tons of iron.”[26]

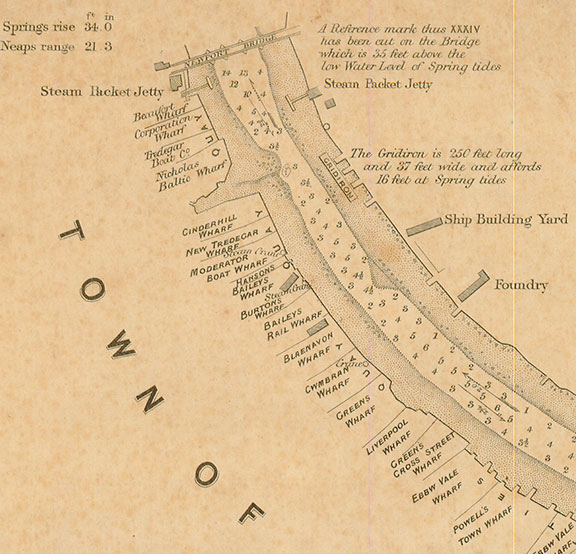

A survey of the wharves near the town bridge in 1870.[27]

The early years of the 19th century saw enormous changes to Newport shipping and the type of ships involved. The first steam locomotive in the world (by Richard Trevithick) ran at Merthyr Tydfil in 1804, and by that time, the early experiments with steamships were already producing results. The American Robert Fulton visited some experiments on steamboats in Scotland in 1803 and built his own designs. He shipped a 24-horsepower Boulton and Watt engine to New York in 1807, where he built his North River Steamboat to transport passengers along the Hudson River, considered the world’s first commercially successful steamboat.[28]

Only nine years later (1816), a Newport engineer and millwright named William Stewart produced a public pamphlet for the people of Newport proposing that they invest in a boat propelled by a steam engine that could carry passengers and goods between Newport and Bristol.[29] This vessel would have replaced the existing arrangements for the weekly market boats and coach travel. His proposal was for a vessel of 70 tons that would require a share capital of £2000. The vessel was to contain accommodation, refreshments, a library and a telescope; passenger fares would be five shillings or two shillings in second class. It is unclear whether this plan ever progressed, but the first steamer to come up the Usk was probably the Bristol-owned Cambria in 1822, providing a daily passenger service between Newport and Bristol.[30] The following year saw the introduction of the Lady Rodney (of just over 58 tons), built in Liverpool for a company of businessmen in Newport and Pontypool. Her master was William Young, and she carried a crew of 8 for her 12 trips per week in the summer (6 in winter) that took 4½ hours on a typical journey. The Lady Rodney operated for 31 years.

The boom in trade in the early 19th century raised the commercial status of Newport to be second only to Bristol in the region, and in June 1822, Commissioners were appointed “for setting out the Port of Newport.”[31] This Commission was granted authority from the Crown to control all shipping of goods in and out of the defined area, to ensure payment of Customs duty, and to prevent smuggling. The limits of the port included the coastline from the river Rumney in the west to Redwick Pill in the east and appointed as lawful a series of wharves in the area where the Riverfront Theatre now stands, including Cinder Hill Wharf and Waterside Wharf occupied by the Moderator Boat Company, Robert Gething and Crawshay Bailey.[32] The findings were adopted and came into force on 1 May 1823, making Newport an independent port.

In 1830, the House of Lords stated: “Very greatly so; in fact, Newport is now the largest shipping Port in the Kingdom, with the Exception of those in the Wear and the Tyne.”[33]

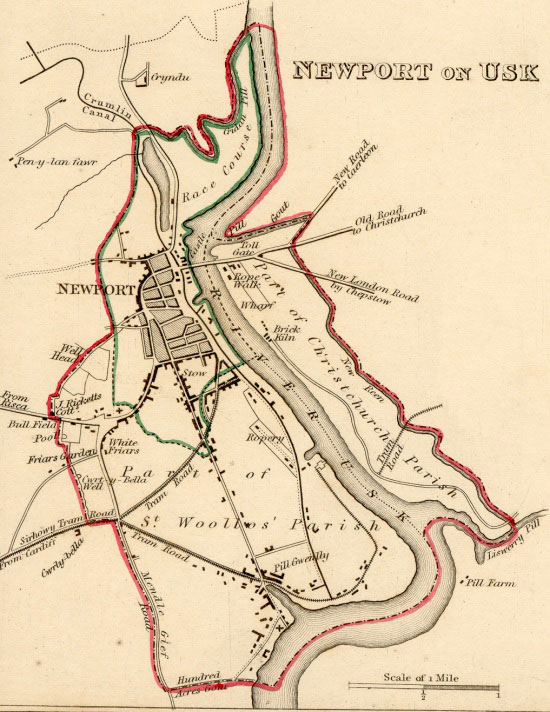

This 1835 plan shows the town just before the construction of the Town Dock, when wharves along the river serviced the ships, and most of Pillgwenlly had not been developed.[34]

The canal can be seen running down from Malpas and through the town close to the river and across Pillgwenlly to the canal basin in Church Street. That basin was abandoned in 1854 and infilled, with the canal's course used as a railway track.[35]

After many years of lobbying, Royal Assent was finally granted on 21 July 1835 for an “Act for making and maintaining a Dock and other works in the Port of Newport, in the County of Monmouth, with a Railway and Stone Road therefrom.”[36] In the following year, the surviving records show the port traffic as follows:[37]

Foreign |

||||||

|

Inwards |

Outwards |

||||

|

Ships |

Tons |

Men |

Ships |

Tons |

Men |

With cargo |

44 |

6,281 |

328 |

189 |

21,137 |

1,258 |

In ballast |

94 |

8,704 |

509 |

8 |

2,003 |

85 |

Coasters |

||||||

Irish trade |

179 |

15,959 |

823 |

1,111 |

97,634 |

5,827 |

Other trade |

1,219 |

73,018 |

2,942 |

6,030 |

319,901 |

19,167 |

Another record from 1835 tells of a trip from Newport to America in record time, when the barque Recovery of Newport (329 tons) arrived from Quebec in 28 days, carrying a cargo of timber for Batchelor and Co. The ship belonged to Mr Joseph Latch, a regular trader with Canada, and her master was Robert Banks. Also dropping some timber at Gloucester, she had completed two voyages to America in 6 months and 7 days.[38]

Newport Harbour Commissioners

In 1836, a body named the Newport Harbour Commissioners was created by statute to oversee the safety, navigational, and environmental interests of the port.[39] Before this, there was no controlling body except the mayor of the borough, who had an ancient right to collect duty from port users. For this, he had to regulate traffic, arrange berths, and oversee unloading. The town's burgesses were exempt from these charges, which only applied to ships from other ports.[40] After some ship owners objected, a government inquiry investigated the management of the river in 1833, and this led to the Commission in 1836.

The Commissioners operate from their offices in Bridge Street. Their area of responsibility is still defined by the Newport (Monmouthshire) Harbour Act 1890 as:[41]

“Those parts of the Bristol Channel and Rivers Usk and Ebbw which lie between an imaginary line drawn in a S.79°W. true direction from Goldcliff until it meets the shore of the Bristol Channel eastward of the Peterstone Wentlooge Church and the bridge over the River Usk at Newbridge and the bridge carrying the South Wales Railway of the Great Western Railway Company over the River Ebbw and the banks and shores of such parts of the said channel and rivers and any works on such banks and shores and all streams, pools, creeks, havens, bays and inlets within those limits.”

The detailed records for one week in October 1838 illustrate the enormous traffic even before the first floating dock was constructed, with 35 ships bringing goods in and 33 leaving. The imports included timber and oats from Quebec, cheese from Gloucester, porter from Swansea, livestock from Ireland, iron ore from Cornwall, and general cargo from London, Bristol, Chepstow and Gloucester.[42] The exports in the same week went to Cardiff, Bristol, Gloucester, Liverpool, Sunderland, Ipswich, Scotland, Ireland, Amsterdam, Rouen and Germany. The bulk of the exports were pig iron and bar iron from several companies, including Blaenavon and Varteg.[43]

A small trading brig entering the Bristol Avon, painted by Joseph Walter in 1838.

Reproduced under Creative Commons licence.

Trade was further enhanced in the 1830s when Newport was approved as a bonding port for wooden goods in 1832 and wine and spirits in 1835.[44] This meant that companies importing goods no longer needed to pay duty on everything at arrival, as some could be stored in yards or bonded warehouses and released later after payment of the duty. The authorised warehouses for wines and spirits were situated on Skinner Street, High Street, Corn Street, Commercial Buildings (Commercial Street) and Market Street. Later warehouses were in Fothergill Street, Market Street, Griffin Street, Dolphin Street, Dock Street, the vaults under Victoria Chambers (Bridge Street), the Masonic Hall (Dock Street) and Baneswell Road.

The Canal at Newport, Monmouthshire c1840, by Joseph Walter (1783-1856).

This painting shows the activity at the canal just before the Town Dock opened, with the ships anchored along the riverside quays and a coal barge on the canal to the left of the lifting bridge.

In the collection of Newport Museum and Art Gallery.

Another feature of the shipping between 1825 and 1850 was a significant influx of Irish workers and settlers from southern Ireland. They usually travelled in coal vessels or cattle ships, which were overcrowded and lacked the required safety equipment.[45] To avoid detection and the anger of local inhabitants, it became common practice to drop off many of these settlers near the mouth of the Usk, from where they had to travel further on foot. The term ‘mud crawlers’ was used to refer to these people. On 21 July 1829, the Monmouthshire Merlin reported the following:[46]

Our correspondent in Newport informs us that the condition of the labouring people is worse than it has been for some years; which he attributed to the numbers of Irish immigrants that come daily by the steam packets from Bristol. Day after day, says he, groups of men, women and children, for the most part without shoes or stockings, are seen parading our streets, begging at tradesmen's shops and houses, and then applying for relief. We trust that perfect tranquillity will soon be restored to our unhappy sister island and in that case the labouring peasantry will, we doubt not, be able to find sufficient employment at home.

A rental and Valuation of Corporation Property in 1836 described the Corporation Wharf as “In a very dangerous and ruinous state”, and in 1842 it was sold to pay the large sum owing to the Council’s biggest creditor.[47] The purchaser was Mr Gething, who paid £1,362 5s. and 9d.[48] Attention now focused on the new Town Dock, which transformed the shipping at Newport.

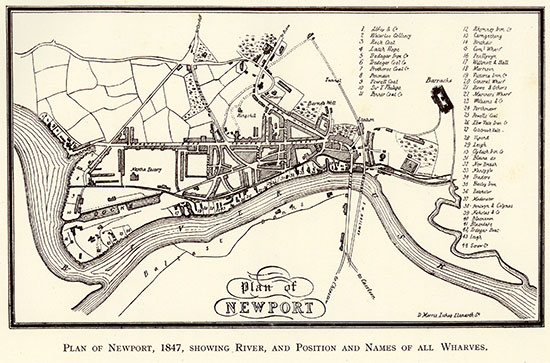

Plan of Newport in 1847. [49]

From "Newport Harbour Commission Centenary 1936" RH John Ltd

This shows the newly opened Town Dock, with the Pill at Pillgwenlly connected to the town by Commercial Road and Commercial Street. The street layout of Pill was filling in, and the Cattle Market can be seen.

References

1 Dawson, J. W. (1932) Commerce and Customs: A History of the Ports of Newport and Caerleon, 49.

Online at: https://archive.org/details/commerce-and-customs-newport

2 Wikipedia – ‘Monmouthshire Canal’; Skillern (1960) ‘The Railways of Newport’,

Online at: https://www.newportpast.com/transport/rail.php

3 Maylan C.N. (1991) Proposed Usk Barrage Initial Archaeological Assessment, GGAT Report No. 91/01, 24-5.

Online at: https://walesher1974.org/her/app/php/herumd.php?level=2&group=GGAT&docid=301464088&linktable=her_source1_link

4 https://www.newportpast.com/gallery/maps/tithe/tithe1.htm

5 Maylan, 1991, 25, citing Gwent Archives D.43.1299

6 Coxe, William (1801) An Historical Tour In Monmouthshire, vol. 2, 415.

Online at: https://archive.org/details/b22011730_0002/mode/2up

7 Newport City Council, Monmouthshire and Brecon Canal.

Online at: https://www.newport.gov.uk/en/Planning-Housing/Planning/Conservation/Conservation-areas/Monmouthshire-and-Brecon-Canal.aspx

8 Reynolds, Paul (1996) Samuel Homfray's coal trains: the Sirhowy Railway in 1821, Railway and Canal Historical Society Tramroad Group, Occasional Paper 109, 6.

Online at: https://rchs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/ERG-OP109.pdf

9 Dawson, 49.

10 Maylan, 1991, 18, citing documentary sources at Gwent Archives.

11 http://www.newportpast.com/nfs/y00t29/y1805.htm

12 Maylan, 1991, 18, citing NLW Tredegar Mss/193-4.

13 http://www.newportpast.com/nfs/y00t29/y1800.htm

14 Dawson, 50.

15 Dawson, 51.

16 Dawson, 53-4.

17 Dawson, 54.

18 Dawson, 55.

19 Dawson, 55.

20 http://www.newportpast.com/nfs/y00t29/y1820.htm

21 Dawson, 55-6.

22 Dawson, 56-7.

23 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chaldron

24 Dawson, 57.

25 Monmouthshire Merlin 15th January 1831, http://www.newportpast.com/nfs/y30t39/y1831.htm

26 Monmouthshire Merlin 26th February 1831, http://www.newportpast.com/nfs/y30t39/y1831.htm

27 http://www.newportpast.com/gallery/maps/river_usk_1870.htm

28 https://www.britannica.com/biography/Robert-Fulton-American-inventor

29 Dawson, 58-60.

30 Dawson, 61.

31 Dawson, Appx II, 143-7

32 Dawson, 62.

33 https://www.british-history.ac.uk/lords-jrnl/vol62/pp1505-1509

34 https://www.newportpast.com/gallery/maps/m1835.htm

35 Maylan, 1991, 19-20.

36 Dawson, 63.

37 Dawson, 65.

38 Newport Past website http://www.newportpast.com/nfs/y30t39/y1835.htm

39 Newport Harbour Commissioners website

40 Dyer, Jim (1987) Newport Harbour Commissioners, Newport Past website (2012)

41 Newport Harbour Commissioners’ website

42 Dawson, 66.

43 Dawson, 66-8.

44 Dawson, 71-2.

45 Dawson, 70-1.

46 https://www.newportpast.com/nfs/y00t29/y1829.htm

47 Jones, Brynmor Pierce (1957) From Elizabeth I to Victoria: The Government of Newport (Mon.) 1550-1850, 135 and 144.

48 Jones, 1957, 146.

49 https://www.newportpast.com/gallery/maps/wharfs1847.html

Back to Index of Peter Brown's "Maritime History of Newport "