St Woolos Cemetery - The Haunted Holy Ground

From the book "The Haunted Holy Ground" by Mike Buckingham and Richard Frame published in 1988.

After Death ... Abundant Life

By Mike Buckingham and Richard Frame

First published 1988

© Mike Buckingham and Richard Frame 2012

It scampers, scuttles, flies and flowers. It’s .... life after death.

For a place that has been put aside for the interment of the dead, St Woolos has an awful lot of life. It is the second largest open space in the borough of Newport and within a single square yard one can count up to seven native species of grass. Perhaps the best memorial of all for the thousands buried in the cemetery is the wildlife, for long after the gravestones have weathered into illegibility the living plants and creatures will still be there.

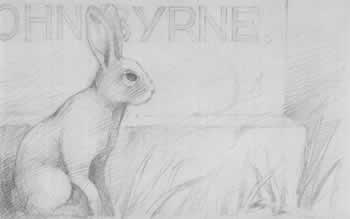

drawing by David Pow

Just like any other town Newport wants to present its best face to the world, and so throughout the borough, publically-owned open spaces are trimmed and manicured for the enjoyment of human beings.

St Woolos is the very model of a prominent public space when viewed from Bassaleg Road, the broad thoroughfare which sweeps past the elegantly arched entrance to the cemetery.

But further back, among the older graves and in places away from the public gaze the grass and the moss grow over weathered stones and the secret denizens of the cemetery make their homes.

One summer evening, about an hour before the pipistrelle bats which live in the seldom-used chapels took wing, we visited St Woolos with Jay Trett, chairperson of the Wildlife in Newport Group, or WING as it is more usually known. As a naturalist Jay was pleased with what she was able to find.

“It’s great that in huge expanses of the cemetery the grass has been allowed to grow. This allows a lot of our native British wild flowers to set seed and thrive here,” she said, while her colleague Sue Bellamy nodded in agreement.

“In the grassy areas we can see the birdsfoot trefoil, two species of vetch and a host of other wild flowers that are disappearing elsewhere as the hay meadows become more scarce.”

“Since the war we have lost something like 90 percent of our hay meadows in this country, so places like St Woolos are vital if these species are to flourish.”

Even as we spoke Sue indentified creepy buttercup, meadowsweet, greater birdsfoot trefoil, crow parsley, hogweed, ragwort, oxeye daisies, wild strawberry, cranesbill, St John’s wort and lesser celandine and as she stalked around flicking the pages of her guide to British wild flowers there was every indication that there were many more to be added to her list of botanical treasures.

Sue thought it would be a good idea if the grass could be cut in July for hay and the hay carted away instead of being let to rot in.

“Wild flowers often like a nutrient-poor soil,” she explained. From the point of view of the wildlife Jay thought things were pretty near to ideal: “But I think it would be a good idea to have some berry- bearing shrubs so that there is sufficient food for the birds and small mammals in winter.”

“Cotoneaster and Pyracantha, both cultivated plants that you often see in gardens, and the Guelder rose, hawthorn and brambles are ideal for this, although too many brambles do tend to spread and force out other species.

“Nevertheless what we have here is a whole food chain. There are plenty of leaves and caterpillars feed off the leaves. Birds like the great tit feed off the caterpillars and domestic cats and hawks feed off the smaller birds ... when they can catch them.”

“I’ve seen seventeen species of bird in an hour-and-a-half in this place: blue tits, great tits, thrushes, robin, house martin, magpies, jays, rooks and other of the more common birds. But I’m sure that being here longer would turn up some more less common types.”

“I would be very surprised, for instance, if there were no green woodpeckers here.”

It is hardly surprising that the Victorians, who planted the Union Jack in just about every corner of the globe brought some exotica back with them. These still to be seen, growing sturdily in the cemetery and offering food and shelter to native creatures. It is easy to be wise after the event and now most of us would conclude that the cemetery would look better if populated by our own familiar beeches and oaks.

And yet some of the foreign trees bring a little of their own atmosphere and have been there so long that we are inclined to accept them. St Woolos is no different from any other British cemetery or churchyard in that yew trees abound.

Both Sue and Jay thought it better had broadleaf trees stood in their place, but accepted that a burial place would not be a burial place without this potent symbol of death, remembrance and rebirth.

“A yew supports about 30 species of plant, insect and animal, which sounds quite a lot,” said Jay.

“Quite a lot, that is, until you realise a native oak can support as many as 300 species.”

But the most intriguing denizens of the cemetery are the small mammals for whom the fifty or so acres represent a whole world. Everywhere there are gravestones which have fallen over and in time gathered generous carpets of moss.

What cosy homes such places provide for the woodmice and the voles who rustle through the cemetery’s long grass all spring and summer, and then in the autumn look to make snug nests, away from the cold winds blowing up from the British Channel. The visitor who is himself prepared to be as quiet as a mouse will be well rewarded. To sit on a gravestone and to watch the cemetery come alive around you is relaxing and rewarding.

“Rabbits like the wider expanses of mown grass and are often to be seen, particularly near the western end. Thrushes and blackbirds share such spots, because the short grass allows them to get at the juiciest worms.

drawing by David Pow

As the day fades and these creatures make for their burrows and their roosts, those who hunt in the night make their appearance. The bats come out to chase insects, just as the last of the daytime birds fly home. Pipistelles, Britain’s most numerous species are common, but it is almost certain that the very much rarer horseshoe and longeared bats live alongside them. Every so often the ghostly white flash of an owl will startle the observer.

There are strange rustlings and hootings and shrieks in the darkness of a cemetery night.

Sometimes, just sometimes, it can be very hard to convince yourself that there is nothing to be afraid of.